The day’s itinerary was packed full of adventure, but I didn’t realize how strenuous our explorations would be until much later. After a hearty breakfast at the hotel, we geared up, donning protective clothing to shield ourselves from the desert sun. I was grateful that I had brought my Columbia hiker boots, necessary for navigating the rugged terrain around Cairo and Luxor. They not only protected my toes from the inevitable encounters with small outcrops of rocks but also provided stability for my ankles.

Anticipation was building as we were about to head out for the day. I had watched countless YouTube videos, some of which warned about the strict rules enforced by the Ministry of Antiquities regarding photography inside tombs. Undeterred, I invested in a high-quality Canon camera, eager to capture the magnificence of these ancient sites. The thought of not being able to document my journey was disheartening, but I was determined to find a way around the restrictions.

Safwat greeted us in the spacious, marbled hotel lobby; his smile was a welcomed sight. He guided us to the waiting van that would transport us thousands of years back in time. As we ventured along the roadway crossing the Nile and eventually leaving behind green fertile fields, Safwat directed our gaze to the hillside on our right. It was a sight to behold. Against the barren, craggy, buckskin-hued slopes, the hill was pockmarked with holes, evidence of ongoing excavations as more burial chambers were unearthed. Scattered among these were the remnants of a village, standing silent to the ebb and flow of civilizations. The homes, long abandoned, whispered the stories of the past, now unveiled to curious tourists like us.

Our driver took us around the base of foothills that gave way to rising canyon walls. We made a right-hand turn, following the blacktop that glistened in the sun like a black snake slithering into the environs of a rocky pit. My attention was drawn to a hilltop that swept by the window. Perched on its crest was Howard Carter’s house, standing like a solitary beacon. Little did the world know that he would forever be remembered for finding the most significant treasure to date, Tutankhamun’s tomb. Carter originally came to Egypt as a hired artist to help record artwork that covered temple and tomb walls. Invited by Egyptologist Percy Newberry in 1891 and learning the science of archeology under Flinders Petrie, Carter, at 17, was on his way to becoming a meticulous, investigative archeologist in his own right.

Carter, inspired by what he saw, decided to stay in Egypt and work various jobs around the country before finally making his way to Luxor. While in Luxor, the excitement of the excavations occurring in and around the Valley of the Kings was as contagious as the California gold rush of 1849. Excavators were vying for digging permits, and only a few were handed out. Carter found work under Theodore Davis, an Egyptologist who unearthed stunning treasures from the tombs of Yuya and Thuya, the great-grandparents of Tutankhamun. Wanting a permit for his own dig, Carter eventually gained Davis’ when, in 1914, Davis retired.

Safwat continued his narrative, explaining why this valley had been chosen for burial sites. He described the ceremonies that were conducted and Carter’s fortuitous find. We reached the visitor center and made our way inside. Walking up to a model of the valley, we familiarized ourselves with the vastness of the burial complex. Below the rendered topography ran shafts underground, showing how far the tombs penetrated the earth. My Midwestern background kicked in and I couldn’t help but connect how the astute prairie dog created similar passages and dens underground. The Egyptians were known for their acute observations of nature and incorporated a lot of their beliefs about the world into their daily lives. They venerated the Scarab Beetle, watching the female dig passageways and chambers into dug balls to lay a single egg. From the chamber, the newly hatched beetle would emerge as if it was reborn. Was it possible that the pharaoh’s tombs mimicked this act of nature?

Sixty-three tombs have been found, but only twelve are open to the public. The Ministry of Antiques can close down a tomb anytime if it suspects that too much pedestrian traffic is damaging it.

From the visitor center, a road stretched further into the rocky outcrops. The tombs began at the end of the road. Trams take visitors the half-mile if they opt not to walk the distance. Seated in the tram, I cringed as I noticed the mobs of people standing near the first tomb. Even though tourism was down due to concerns about the Israeli and Hamas conflict, there were still pockets of heavy tourist traffic. Making our way past the crowds, Safwat suggested that we start with Seti’s tomb. “It will have the least number of visitors since it’s further into the canyon,” he explained. I appreciated Safwat’s unfailing strategy for obtaining the best touring experience.

Our footsteps crunched on the wide stone and dirt path, kicking up small clouds of dust. Limestone formations rose around us. I glanced at the bright blue sky, thankful that mid-February was a comfortable month for exploring the valley, but I knew temperatures would reach the upper 80s later that day. Seti’s tomb was located just off the main valley floor. A ticket monitor was waiting at the entrance. Seti’s tomb is an extra charge. Safwat gave us a brief overview of what to look for inside the tomb. He would not join us inside. “Take your time,” he assured us. He would guide us to the next tomb when we were ready.

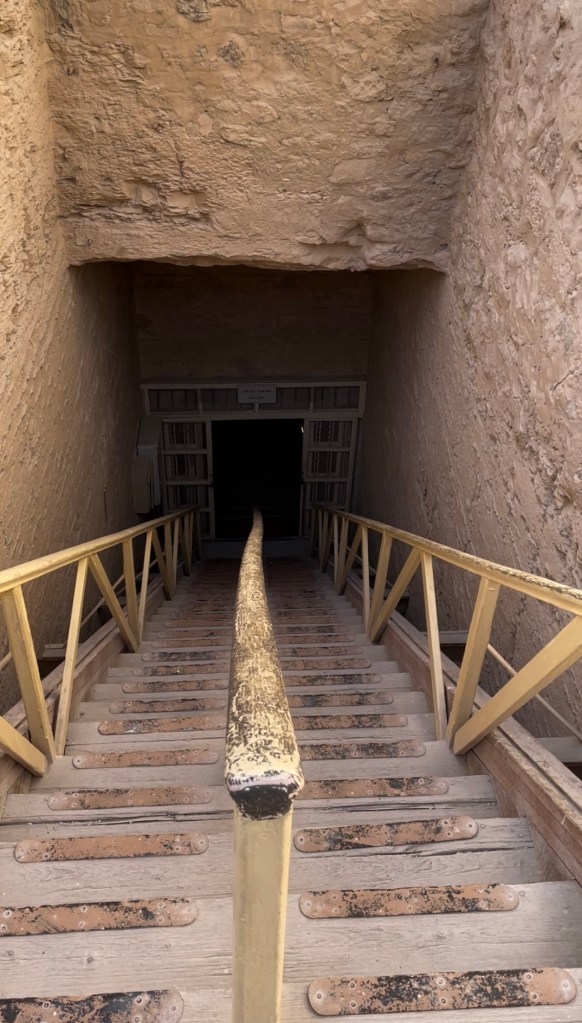

The tomb entrance was elevated off the ground. We climbed up a few steps, showed our tickets, and then descended into a long shaft. Wooden stairs and handrails were built to provide easy and safe access. Well-lit, the shaft was wide, the ceiling high enough for most adult men and women. The steps transitioned into wooden ramps. The walls were chiseled, bare limestone slabs that eventually displayed colorful drawings of Egyptian life and beliefs practiced over 3,000 years ago.

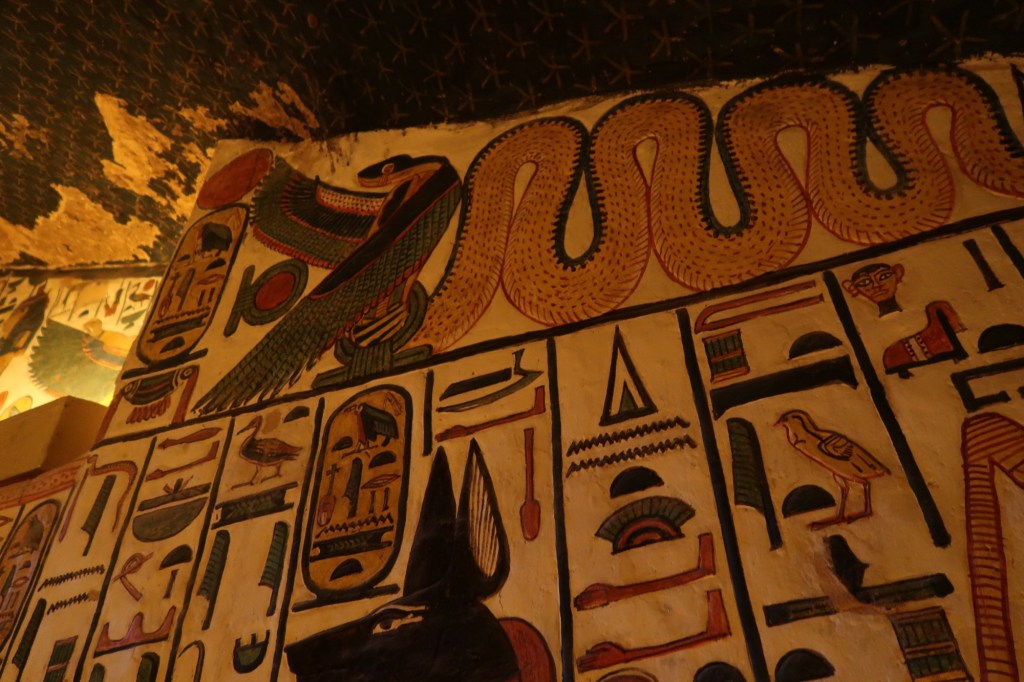

The ceiling was a jigsaw puzzle of half images colored in navy blues, terra-cotta reds, sage greens, and yellows. I couldn’t guess what they must have been, but kneeling below the ceiling on a painted beam was the goddess Maat. Depicted at most tomb entrances, her outstretched arms, draped in falcon feathers, seemed to lovingly embrace those who entered the tomb. Her purpose, however, was to keep cosmic order, assuring that Truth, Rightfulness, and Justice prevailed.

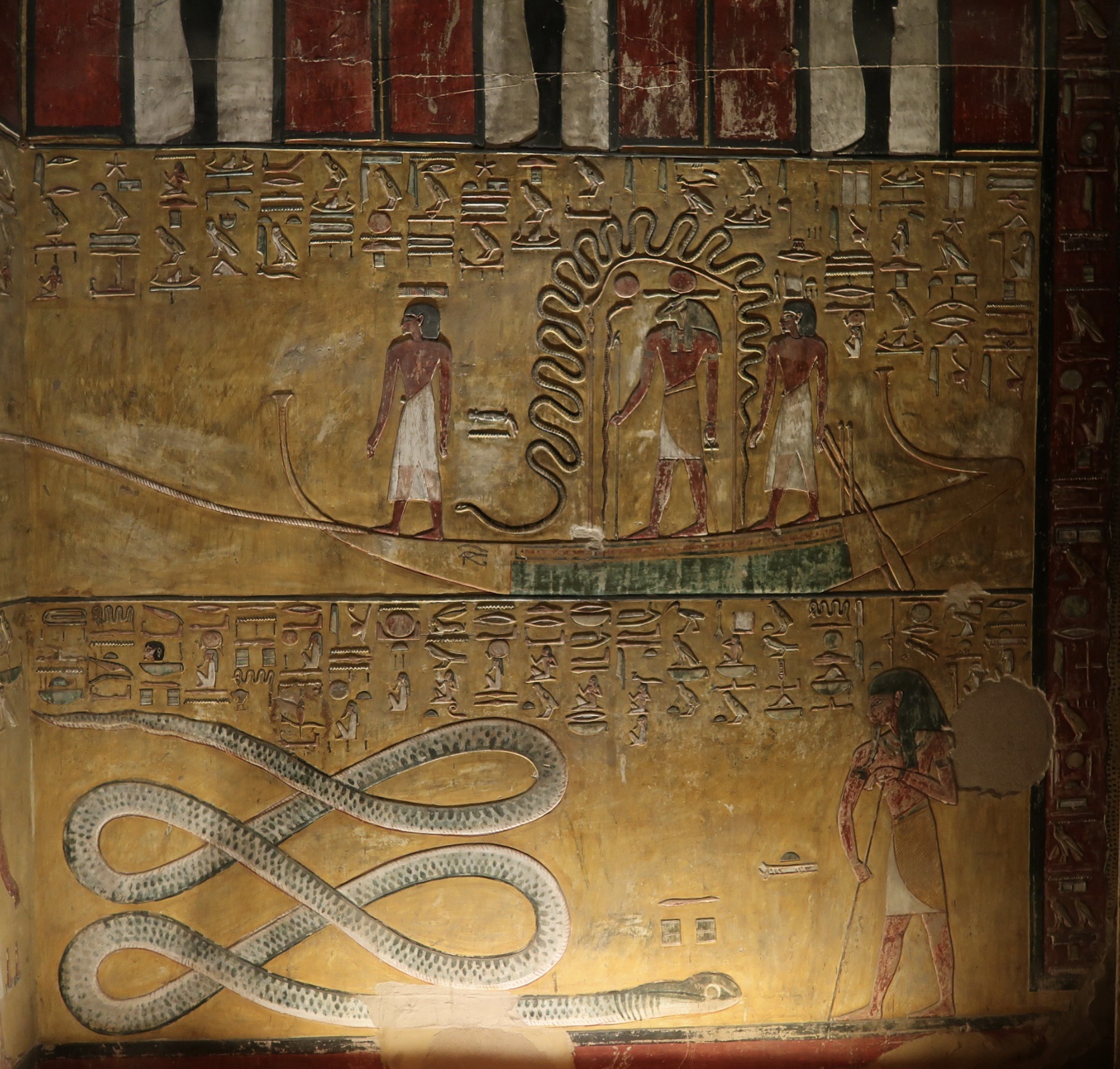

As we progressed further into the tomb, the artwork became more pronounced, presenting us with a dazzling array of colors and images. The sheer magnitude of it all was overwhelming, and I had to pause for a moment to adjust. On my right, moving towards me on the wall was a three-headed serpent lifted off the ground by its legs. My progress through the tomb seemed to play tricks with my eyes and I was glad to leave the serpent behind. Hieroglyphs cascaded down the wall from the ceiling. Images of servants laboring for the deceased were engraved onto the walls, and gods and goddesses presided over the formal steps to be undertaken when entering the underworld.

We finally approached a vast chamber with several decorated pillars. On the pillars were life-size images of the Pharaoh, Seti I, standing with the gods. I felt as if I had unwittingly barged into an assembly where a discussion was taking place between mortal and god and where Egyptian men lined up on every wall were ready to act on the Pharaoh’s bidding. The opulence and grandeur of the room, along with the deep blue ceiling studded with golden stars, left me speechless, and it seemed to have this effect on everyone touring it. A few visitors wandered into the chamber, circling the pillars, taking in the images. There was a hush. No one wanted to break the magic that somehow hovered there.

To the left, another passage continued its descent into the ground. A long corridor led to another chamber painted more brightly than the first. Golden hues dominated the walls, the ceiling in rich blue had an entire story painted on it, and more pillars occupied the room. The walls were richly decorated with images of solar boats making the journey to the underworld. Gods and goddesses were present to help with the trek and more writings in the form of hieroglyphs donned the walls. A docent casually stood on the periphery of the room and thankfully did not object to my photo taking.

I learned later that there are seventeen chambers in Seti’s tomb. A few branched off of the golden chamber. They were closed off as excavations in these rooms were still taking place. There were other tombs to explore, so we began our ascent out of the tomb into the bright sunlight. Safwat led the way to the next tomb. It was Tutankhamun’s.

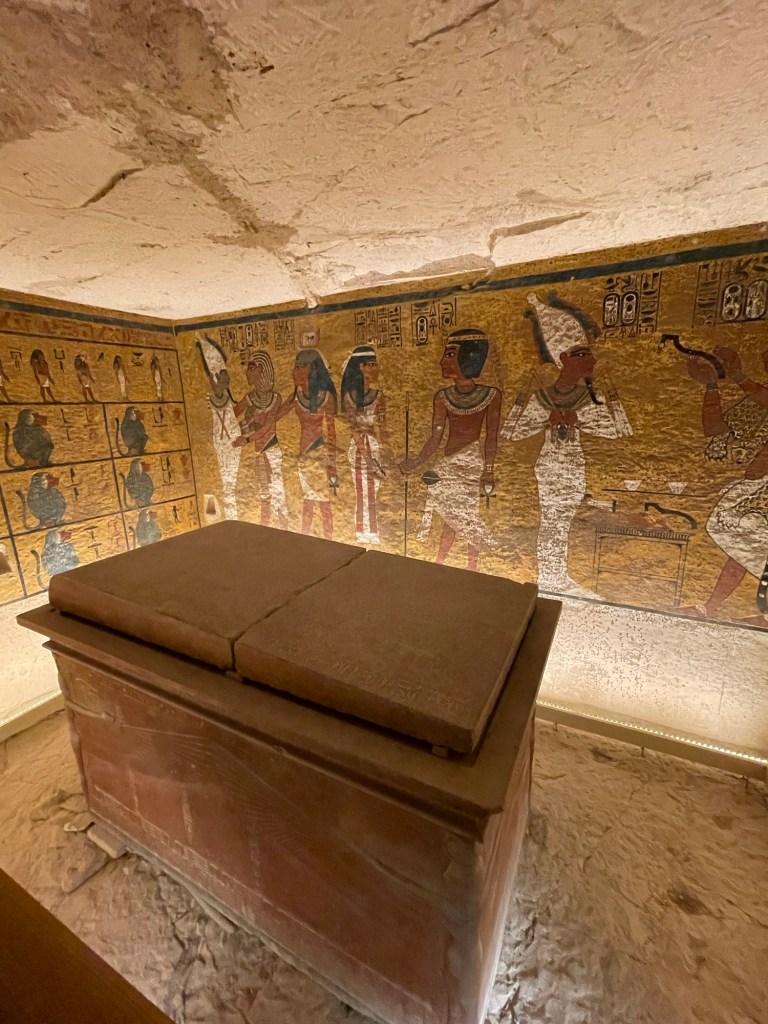

Because the tomb was small, we spent the least amount of time in it. It was hard to believe that such vast amounts of treasures were extracted from it. Carter had cataloged 5,000 items. To even find the tomb was an amazing tale. Rubble from other digs had covered King Tut’s burial site to such an extent that Carter had railroad tracks laid down and cars used to carry out thousands of tons of dirt. Then WWI began, shutting down the excavation for a while. When Carter got the go-ahead and started work, his sponsor, Lord Carnarvon, was ready to pull funding. But the signs that a tomb was nearby were too great to give up, and Carter convinced Carnarvon to fund him for one more year.

Today, the hard work of laborers, the persistence of archeologists, and those men and women who funded these excavations allow us to glimpse into the distant past and wonder about those who came before us. My amazement continued as I later entered the three tombs included in the general admission for the Valley of the Kings. Ramesses I, III, and Ramesses VI were spectacular. These tombs have protecting glass or guardrails along the walls because they are the most visited.

I was impressed by the cleanliness of the tombs. Despite the constant flow of pedestrian traffic, the tombs were in excellent condition. We ventured into long, deep passageways, yet the air was fresh and not stale. Later, during our tour of Nefertari’s tomb in the Valley of the Queens, I learned that the tomb had an air system installed, which helped to regulate humidity and protect the delicate paintwork from damage.

The Valley of the Queens is less popular among tourists. One reason is that most riverboat tours have a tight schedule and don’t include it in their itinerary. We packed ourselves into the van and drove to the area only a mile away. I was thrilled to see that this valley was less crowded. A security office in the form of a small glass and stone structure sits at the entrance of the valley. Our bags were searched, and we were cleared to go. Walking along a wide path, we approached Nefertari, one of the most hard-to-get-into tombs. Entry was limited to a few visitors at a time, with an allowable 10 minutes inside the tomb. The tomb was an extra charge of 2,000 Egyptian Pounds which converted into sixty-six dollars for a ticket.

Nefertari held the esteemed title of Grand Queen and was the beloved wife of Ramesses II. Despite his multiple wives, she was his favorite. Nefertari and Ramesses II married before his ascension to the throne. She played an active role during his reign, engaging in diplomatic discussions with leaders from other nations. She was politically astute, highly educated, and beautiful, earning admiration from her husband. A testament to their love is written on the monuments at Abu Simbel, depicting her alongside Ramesses II at equal standing, with the inscription reading, “For whom the sun doth shines.”

Her tomb attests to Ramesses’ adoration. It is the most elaborate tomb I have encountered. Ernesto Schiaparelli, who was the director of the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy, discovered the tomb in 1904. However, the tomb remained closed to tourists until 1995. Today, the tomb is subject to periodic closures to preserve the delicate and elaborate artwork on the walls and ceilings.

Our initial reaction can best be described as incredulous. The bland landscape outside contrasted sharply with the explosion of colors in the tomb, leaving us utterly speechless. Our friends just had to ask, “Have these paintings been retouched?” The answer was “no”. I could now marvel at the reference by archeologists who called Nefertari’s tomb, “The Sistine Chapel of Ancient Egypt.”

Academics remark that the tomb has the best preserved ancient depiction of the journey toward the afterlife, with passages from the Book of the Dead written on the walls. Images of near-life-size gods and goddesses and Nefertari on the walls and pillars in the chambers seemed to fill the rooms with inanimate activity. Deep golds for the background on the walls and midnight blues on the ceiling made the reliefs and hieroglyphs pop out. I was honored and privileged to enter this sacred sanctuary.

My musings were abruptly interrupted, however, when, while recording my leave of the tomb, a low, bellowing voice rose, saying, “No Video!” I couldn’t help but be startled. The constraints of filming finally caught up with me. I politely put my camera down, but not without capturing those few precious memories.

Safwat was waiting patiently outside when we emerged into the bright sun. He enthusiastically gestured with his hands that it was time to relax and have a wonderful lunch. We were all for that. Leaving the valley behind, we found ourselves at the edge of cultivated fields. Tucked away among palm trees was a group of flat-roof buildings. We drove into the center of them and got out. The place looked like someone’s farm, and we were slightly confused. Safwat guided us further into the grounds, where brightly decorated tables sat under a thatched roof. “This is my favorite place,” Safwat told us. “Let me recommend the duck, but please feel free to ask questions about anything on the menu.”

The food was indeed tasty. There is something about sharing a meal that puts people at ease. We were passing around bowls of zucchini, beans, stewed duck, and fresh, crisp salad when my girlfriend asked a question that had been nagging at her. “What are your thoughts on Americans coming over here since Hamas and Israel are fighting?”

Safwat, in the midst of sharing his scraps with a persistent cat, paused for a moment. “I don’t like to see anyone fighting, hurting others, getting killed. I honestly don’t know why there has to be this hatred rearing its ugly head between the Palestinians and Israelis. If they really wanted to find a solution, they would have done it by now. A lot of people think it’s about money. War is money, and the rest of us pay for it. If you ask if I feel animosity towards the Americans, I don’t; most Egyptians don’t.”

The State Department’s travel advisory on Egypt was a Level 3, “Reconsider Travel”. I had discussed with our friends the possibility of canceling our trip, but fortunately, it didn’t come to that. After lunch, Safwat gave us a farm tour, showing us where herbs dried in the sun, and a clay oven was used to bake bread. There was a kindergarten and childcare room where a few toddlers gazed at us in wonder as they sat on a dirt floor in front of a chalkboard. Goats and dogs roamed around the grounds.

After leaving the farm, I had difficulty focusing on our next tour. The conditions I witnessed were the bare necessities of life. Water came out of a well or from bottles that were shipped in. Electricity was questionable. How was it that there were still places of extreme inequity?

Our day was only half finished. Walking through the ruins of the Mortuary of Queen Hatshepsut, Medinet Habu, and finally relaxing on a felucca for a late afternoon sail was still ahead.

A few notes:

As of March 2024, according to Earthtrekkers.com, Nefertari’s tomb was closed indefinitely.

Photo/film taking is a hit-or-miss opportunity. Depending on the docent monitoring the tomb, policies were flexible.

The Valley of the Kings and Queens both have a security checkpoint for entering the monuments.